The methodological procedures of phase I resulted in the P2MIR 1.0, an intervention culturally and contextually adapted to the Portuguese healthcare context, while preserving the fidelity of the original intervention’s PCC principles and structural coherence. Furthermore, the findings yielded critical insights to inform the following phase. In this regard, Steps 1, 3, and 4 were identified as essential to preserve the partnership between healthcare professionals and patients and therefore remained unaltered, whereas the remaining steps were considered amenable to context-sensitive adaptations to enhance local feasibility. In phase II, co-designed steps were implemented over four focus group discussions [41, 50]. Eighteen stakeholders were invited to participate, but one patient did not respond. In total, 17 participants (registered nurses and physicians: n = 11; patients who had experienced a myocardial infarction in the past four months: n = 6) were engaged with the study’s purpose in a trusting and safe environment, ensuring meaningful and focused discussion (Engage). While the study protocol [44] initially aimed for 16 healthcare professionals and 5 patients, following Krueger et al. [50], the lower number of professionals resulted from availability and organizational constraints, and the inclusion of an additional patient is considered a positive outcome. Data saturation was achieved, with no new themes emerging in the final focus group. The richness of subcategories within precoded themes further supports the depth of insights, aligning with guidance suggesting saturation may be reached with a small number of groups when the sample is homogenous and the research question focused [51]. Conducting two focus groups per stratum follows recommended practice [51]. Sociodemographic, professional, and clinical data are presented in Table 2.

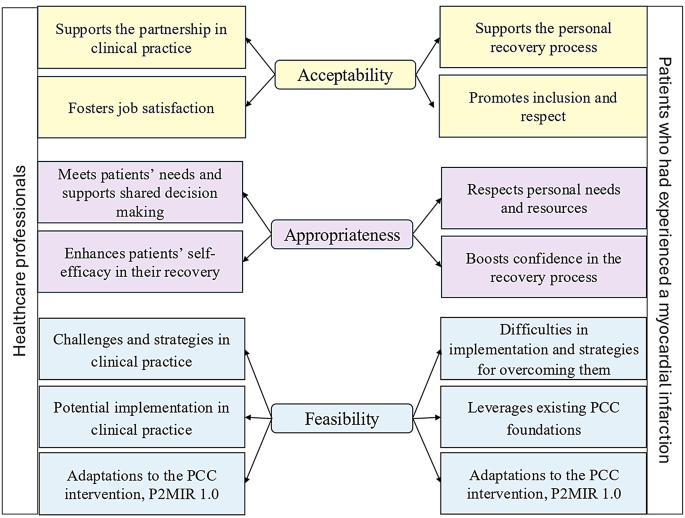

Stakeholders’ perspectives were instrumental in gathering and assessing the perceived acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility of P2MIR 1.0, as well as in identifying areas for improvement—whether as potential users (patients) or providers (healthcare professionals) of the intervention (Plan and explore) (Fig. 2). To enhance the transparency of the results, quotations from the participants were included and identified using codes corresponding to the focus group discussions (FGD 1 to 4).

Coding scheme for healthcare professionals’ and patients’ perspectives of the PCC intervention (P2MIR 1.0)

Healthcare professionals’ perspectives

Acceptability

‘Supports the partnership in clinical practice’

Healthcare professionals described the PCC intervention as aligned with the building of partnership with patients in clinical practice. Though PCC supports recovery is often perceived as time-consuming “extra care”, they saw it as potentially time-saving by addressing personal needs early and reducing fragmented communication.

In my daily work, I feel pressured not to do what I want to do: practice Nursing. I don’t think I’m the only one feeling this way! Because I must be quick so that patients can come in and leave quickly to make way for the next one. (FGD 1)

‘Fosters job satisfaction’

Healthcare professionals highlighted that the PCC intervention was seen as a potential source of job satisfaction because it reinforced the core principles of caring. Knowing that care was more closely aligned with patients’ needs and improved the quality of care fostered a sense of personal fulfilment and professional recognition.

And I’m really leaving here feeling proud to be a nurse, because I think that’s what it’s all about. We need to demonstrate what we do and put it into practice, and that’s how we succeed. (FGD 1)

Appropriateness

‘Meets patients’ needs and supports shared decision-making’

Healthcare professionals deemed the PCC intervention as suitable for addressing patient needs and facilitating shared decision-making. They noted that an exclusive focus on clinical parameters risks marginalizing patients’ experiences and personal narratives. Although person-centred principles are embedded in European cardiology guidelines, they were not consistently operationalized in practice. Consequently, the PCC intervention was perceived as a means of enhancing patient engagement and fostering collaborative care in alignment with these guidelines.

I think it makes perfect sense, and it’s a sign of the times. (…) Much more than before, things are centred [on the person], and ensuring that patients are properly informed is now almost the most important thing. And we have an obligation to inform them properly. (FGD 2)

‘Enhances patients’ self-efficacy in their recovery’

Healthcare professionals reported that the PCC intervention could enhance patients’ self-efficacy by providing structured support for lifestyle changes and addressing uncertainties in real time. Co-creating health plans based on individual resources was seen to foster autonomy, while encouraging daily activities was considered beneficial in reducing anxiety, especially related to physical limitations or symptom fears. The intervention was viewed as particularly valuable for patients with lower educational levels, as tailored follow-up could strengthen condition management.

Of course, I think it makes perfect sense. I believe it will make patients feel safer. Above all, patients need to know that the healthcare system extends beyond the hospital and is committed to their care. (FGD 2)

Feasibility

‘Challenges and strategies in clinical practice’

Implementing the PCC intervention appeared feasible, although participants identified time constraints and workforce shortages as key barriers. These were compounded by a predominantly disease-centred care model and brief hospital stays, particularly for myocardial infarction patients. Poor coordination with primary care was also noted; however, an organizational restructuring was already underway to address this issue by enhancing communication pathways.

This type of approach requires greater availability in terms of time and mindset (…). We do this informally, we all know it’s very important. (FGD 2).

Education and training were seen as essential for enabling PCC implementation by fostering awareness, clarifying roles, and promoting stakeholder commitment and motivation.

I think it’s necessary to have an initial phase to present this programme and provide training, so that everyone is familiar with its structure. (FGD 2).

‘Potential implementation in clinical practice’

Despite the challenges, the PCC intervention was recognised as feasible for implementation in clinical practice, mainly because the partnership assumptions were based on authenticity and attention to patients’ needs at each moment, rather than on the amount of time spent with them.

In terms of time, we need to be present (…) Perhaps we should try to engage more. (FGD 1)

From an organisational perspective, healthcare professionals agreed the intervention seemed feasible. Step 1 (‘Initiating the partnership’) was considered the most time-consuming phase; however, the nurse–patient meeting 24 h post-admission could be adapted to include the PCC approach, enabling co-creation of the health plan. Over time, both professionals and patients were expected to find the process easy to implement and regard it as equally important as other core clinical activities.

It’s part of the initial assessment. We always do it within 24 h, right? So, I don’t think it would change anything; the document just needs to be more specific. (FGD 1)

Patients’ perspectives who experienced a myocardial infarction

Acceptability

‘Supports the personal recovery process’

Patients perceived the PCC intervention as pottentially beneficial to their recovery, citing its provision of timely, relevant information and its role in facilitating integrated care across the three levels of the healthcare system – hospital, outpatient and primary care – thereby reducing anxiety stemming from informal sources.

I realised that the nursing staff at the hospital (…) is very well prepared. They are experienced, too. I don’t know how many years of experience they have – some may have 2 years, while others may have 20 years – but they are very well prepared. Some of them are more ‘psychologists and psychiatrists’ than certain trained psychologists and psychiatrists. (FGD 4)

‘Promotes inclusion and respect’

Over time, care provided through the PCC intervention could enhance patients’ involvement in their own recovery and help them feel more respected and included. Patients expressed a wish to have received such care, especially during the first two months after the myocardial infarction, a period of heightened vulnerability due to uncertainty about their condition.

I did everything on my own initiative, but I would have really liked someone to be there for me, to help me take the steps. (FGD 3)

Appropriateness

‘Respects personal needs and resources’

The PCC intervention seemed appropriate for addressing personal needs and recognising individual resources. They expressed a preference for being asked what mattered to them, rather than receiving generalised advice that overlooked their expectations. Co-creating health plans with professionals was seen as a way to ensure their needs were acknowledged. One patient noted that experiencing a myocardial infarction brought greater objectivity and a renewed sense of purpose.

This is all part of the need to have a structured plan (…) over time, we must set new objectives and understand our reality day by day. (FGD 3)

‘Boosts confidence in the recovery process’

Establishing a partnership with healthcare professionals, alongside a structured health plan throughout the patient’s journey, was perceived to enhance confidence in recovery. Following myocardial infarction, concerns emerged around lifestyle changes, social roles, routines, and sexual activity. Limited access to timely information increased anxiety and led to unplanned care. While high health literacy supported self-management to some extent, those with lower literacy were seen as more vulnerable to inadequate support.

There’s no follow-up at all. The follow-up that occurred was on us! (FGD 3)

Feasibility

‘Difficulties in implementation and strategies for overcoming them’

Patients identified time constraints and overburdened staff as key barriers to implementing the intervention, but suggested these could be addressed through effective organisational management. Changing entrenched practices was seen as the greatest challenge, while success was linked to efficient time and workforce use. The PCC intervention was considered cost-effective, requiring minimal additional resources.

It’s clear that they are really overloaded with work. (FGD 4)

‘Leverages existing PCC foundations’

The PCC intervention appeared to be feasible, building on existing practices to support consistent delivery. Patients expressed a need for more person-centred care and recalled feeling valued during interactions with engaged staff, despite workload pressures. One patient described how staff’s attentiveness and active listening created a supportive environment during his/her hospital stay. Another recounted that face-to-face contact with the cardiologist at the outpatient unit genuinely enhanced his/her sense of security and confidence.

This whole concept has already been partially implemented. (…) The nursing and assistant staff were very approachable, positive, and helpful, which goes a long way for patients who are hospitalised. (FGD 4)

Proposed key adaptations to the P2MIR 1.0

The areas of P2MIR 1.0 proposed by the stakeholders as requiring contextual improvement in Portuguese real-world settings were consolidated into two key adaptations, aimed at addressing their needs and preferences (Develop). These key adaptations emerged organically through stakeholder engagement, revealing notable similarities in perspectives across both healthcare professionals and patients.

A PCC-based post-discharge phone call

Healthcare professionals noted that short hospital stays following myocardial infarction often left patients psychologically unprepared for self-management. Patients expressed similar concerns, describing feelings of isolation, uncertainty, and fear of sudden symptoms. One patient, for instance, recounted an emergency visit triggered by misinterpreting the size and appearance of a haematoma. Although their standpoints differed—providers observing from a clinical lens and patients speaking from lived experience—both groups arrived at the same conclusion: a PCC-based post-discharge phone call was essential (Table 3).

I would say that the first 48 h after discharge are essential, and this does not exist (…) [healthcare professional].

It reassures me to know that I can call a specific number if I feel unwell and speak to someone who has immediate access to my medical records. (FGD 4) [patient].

Peer support groups

Patients noted that focus group discussions provided insight into others’ challenges and coping strategies, which strengthened their confidence in managing recovery and underscored the role of peer support in enhancing self-efficacy. The inclusion of individuals who had experienced myocardial infarction within the previous four months highlights the relevance of such support during the early recovery phase. Table 4 summarises patients’ suggestions for refining the intervention regarding the peer support groups.

Being able to share my experiences and receive information from all of you – it was good for everyone. I have no doubt about it! (FGD 4)

Because I also understand your experiences and all the feedback. (FGD 3)

The original intervention also included a phone call from the primary care health team after discharge (included in Step 5) to confirm the referral and arrange a meeting before the scheduled 8-week post-discharge visit, if necessary. Nevertheless, maintaining the existing partnership with hospital professionals was perceived as a more personal and effective method of enhancing well-being and security by both healthcare professionals and myocardial infarction patients. Consequently, upon receiving confirmation from the developer of the original intervention that Step 5 could be refined without compromising its core, the telephone contact from the primary care team was deemed unnecessary at this stage.

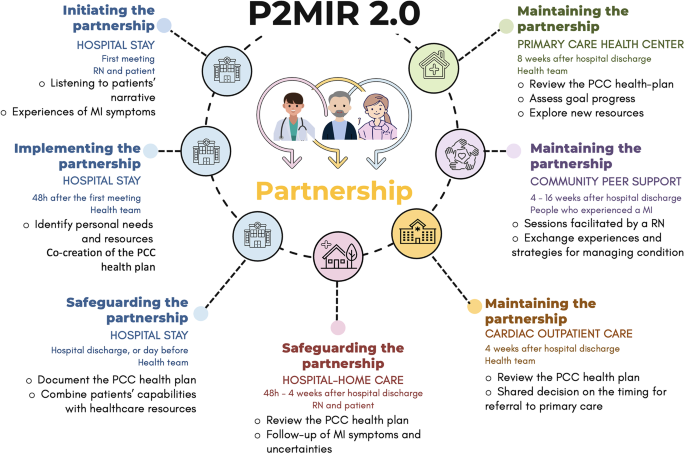

Co-design of P2MIR 2.0 intervention

The proposed key adaptations by the stakeholders were translated into two actionable components that were co-designed with the stakeholers (Decide). These components reflected the principles of the GPCC ethical model that guided the original intervention and contributed to reinforcing collaborative relationships between healthcare professionals and patients. Although, while the original intervention adopted the term working the partnership, as introduced in the GPCC model’s first publication in 2011 [52], the P2MIR 2.0 adopted the updated terminology implementing the partnership, as used in a more recent 2021 publication [15], which confirmed the concept remained unchanged (Fig. 3).

Safeguarding the partnership at a distance

Patients continue to benefit from PCC after hospital discharge through a combination of remote and in-person support to address uncertainties and monitor symptoms. This care is provided by the registered nurse who established the partnership with the patient, and it includes a direct telephone line that patients can use if necessary (hospital-to-home care).

Maintaining the partnership in the community

Following hospital discharge, patients can join peer support groups within the community, either in person or remotely. These groups are facilitated by a registered nurse from the cardiac outpatient or primary care unit.

Finally, those new componentes were integrated into version 1.0 (Change), alongside those retained from the original intervention, leading to a new version—the P2MIR 2.0. (Fig. 3).

The Portuguese version of the Person-centred care intervention to enhance self-efficacy in patients following a myocardial infarction (P2MIR 2.0). Legend: MI: myocardial infarction; PCC: person-centred care; P2MIR: Portuguese version of the Person-centred care intervention to enhance self-efficacy in patients following a myocardial infarction; RN: registered nurse

In summary, developed through a two-phase approach, the P2MIR 2.0 represents an adaptation of the original intervention with the purpose of enhancing patient self-efficacy following myocardial infarction. In Phase 1, the original intervention was methodologically transferred to the Portuguese healthcare context, resulting in P2MIR 1.0. Subsequently, using a qualitative methodology, version 1.0 was co-designed with stakeholders to ensure alignment with the stakeholders prespectives, culminating in the final version—P2MIR 2.0.

link